A New Law and a New Way Forward?

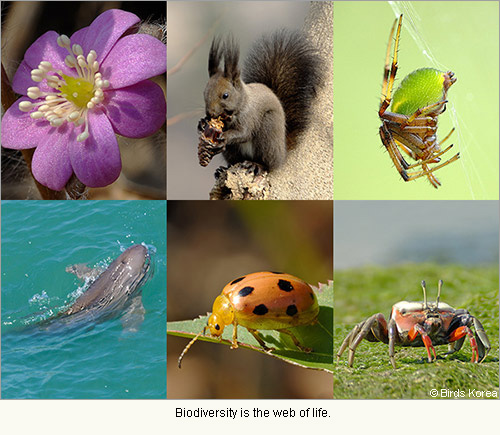

2010, the United Nations-designated International Year of Biodiversity, was to be the year by which the rate of global biodiversity loss was to be reduced. This target has not been met.

In the words of the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, “In 2002, the world's leaders agreed to achieve a significant reduction in the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010. Having reviewed all available evidence, including national reports submitted by Parties… the target has not been met. Moreover…the principal pressures leading to biodiversity loss are not just constant but are, in some cases, intensifying. The consequences of this collective failure, if it is not quickly corrected, will be severe for us all.” (Foreword, Global Biodiversity Outlook 3).

The world’s nations are failing to conserve biodiversity. And there is an increasingly urgent need to challenge “the principal pressures leading to biodiversity loss” in order to head off “severe” consequences.

Apparently in response to this growing biodiversity crisis, a new “Act on Preservation and Use of Biodiversity” is being drafted by the Ministry of Environment. (see: "Draft bill of Act on Preservation and Use of Biodiversity").

This new legislation is needed to help the nation correct some of the “failure” and to build on some of the positive steps that have been taken over the past few decades.

Positive steps in the Republic of Korea have included, for example, the designation of some species as National Natural Monuments and of protected areas, with “about 2.8% of the national territory, or 2,801.1 km2…designated as protected areas after the CBD COP-7 in 2004” (Fourth National Report to CBD). They have included the signing-on to the Ramsar Convention, to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and to bilateral Agreements like the Republic of Korea-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement. They have included the development of UNDP-GEF supported initiatives on Wetland Biodiversity and on Reducing Environmental Stress in the Yellow Sea Large Marine Ecosystem.

And probably the most important step forward of all has been the greatly increased public understanding of the need for conservation, achieved through a combination of the above, and by the tireless work of NGOs, educators and responsible media and decision-makers.

While it might be easy to agree on these successes, identifying the “failure” in present policy and legislation is, it seems, rather more controversial.

Globally “The five principal pressures directly driving biodiversity loss” are “habitat change, overexploitation, pollution, invasive alien species and climate change” (Executive Summary, Global Biodiversity Outlook 3).

Within the Republic of Korea, we believe that “habitat change” (habitat loss and degradation) is the most immediate and widespread of these pressures. And the root causes of habitat change are woven into the fabric of the present development model.

Habitat for Biodiversity

For example, despite the growing public interest in birds and the natural environment and the increasing number of Protected Areas, there are still no bird reserves or nature reserves in the Republic of Korea. There is, indeed, no area that Birds Korea is aware of that is being managed primarily and permanently for biodiversity. Almost all biodiversity-rich areas, whatever their status on paper, still seem to be vulnerable to development-driven policies, be it through inclusion in special development zones for industry or new housing, or for tourism infrastructure.

Stretches of natural coastline continue to be concreted or reclaimed, in contradiction of the formal government commitment made in 2008 that “intertidal mudflats should be preserved and that no large-scale reclamation projects are now being approved in the Republic of Korea” (Ramsar Resolution X.22). Rivers continue to be dammed and dredged on a huge scale, most recently as part of the Four Rivers Project. Forests continue to be cut, with almost 200,000 ha of forest area lost nationwide between 1978 and 2007 (Fourth National Report to CBD, p. 8). And even large areas of rice-field continue to be built on, with 18,215 ha and 22,680 ha of agricultural land in 2008 and 2009 respectively converted “into roads, rail roads and factories” (Yeonhap News, June 29th, 2010).

The huge Saemangeum reclamation is one of the most striking examples of the failure of existing policy and legislation to conserve the nation’s most bio-diverse ecosystems.

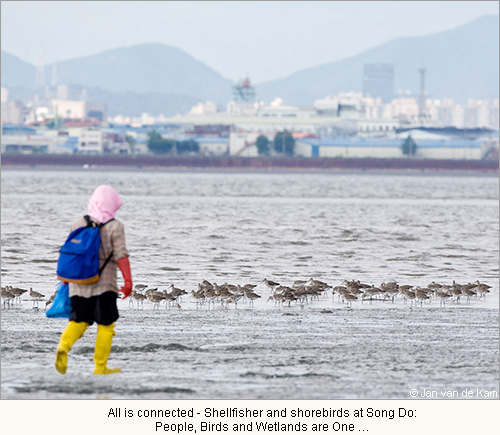

Based on government data (as well as our own), the Saemangeum estuarine system was the single most important known site for shorebirds in the nation and in the Yellow Sea. Because of its exceptional natural productivity, this vast estuarine system also supported the livelihoods of more than 20,000 local people. Despite existing obligations to CBD and Ramsar and years of court cases, Saemangeum’s national and global importance for biodiversity was not enough to prevent the construction of a 33-km seawall, which was closed in 2006 and now dams off the sea. What remains now at Saemangeum is a vast reclamation lake and desert-like tidal-flats. There is no “eco-city” there yet, and most remains unbuilt on. Much of the system therefore could be restored if tidal-flows were restored, even now. Yet there are still no plans to do so. The 40,000 ha of natural wetland now being destroyed at Saemangeum is equivalent in area to the forest nationwide being lost every four years, and to the area of agricultural land being lost nationwide every two years. The impacts on biodiversity are of course disproportionately even larger.

Even Ramsar sites are not safe from “habitat change” either. Since Ramsar Site designation, wetlands at Muan, Upo and Suncheon Bay for example all have increased infrastructure and new parkland and visitor centres, losing some of their “ecological character” in the process.

Photo © Birds Korea

According to Ramsar Article 2.2, “Wetlands should be selected (as Ramsar sites) on account of their international significance in terms of ecology, botany, zoology, limnology or hydrology”. The primary purpose of Ramsar sites is to conserve this international significance and the natural functions of wetlands. The primary purpose is not, for example, to maximise income from tourists at the cost of biodiversity loss. All the same, both Suncheon Bay and Upo (along with the DMZ) are now targeted for further development as “large-scale eco-tourism attractions” in recent proposals set out by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (KBS, July 15).

While data on the impacts of biodiversity of all of this rapid habitat loss, degradation and disturbance remain poor or incomplete, many bird species do appear to be in decline.

Photo © Richard Chandler

Photo © Tim Edelsten

Photo © Robin Newlin

Photo © Jan v.d. Kam

In some cases, such as at Saemangeum, the impacts of habitat loss on species like the Great Knot Calidris tenuirostris, the now Critically Endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus and on many other species of shorebird have been made clear by the Saemangeum Shorebird Monitoring Program. It is no coincidence, considering the large number of large-scale reclamation projects in recent years, that several other species ecologically dependent on inter-tidal wetlands, such as the globally Endangered Black-faced Spoonbill Platelea minor and the globally Vulnerable Chinese Egret Egretta eulophotes also have a poor national and global conservation status.

However, the range of threatened or declining bird species is not confined to one habitat type alone, of course. Many bird species of rivers, of freshwater marshes and rice-fields, of agricultural areas, of forests and of islands appear already to be in decline and are threatened by further large-scale habitat loss and degradation.

The declines in these species indicate negative changes to the same natural environment that we also depend on for life and livelihood. Drainage of wetlands, concreting of streams, cutting of forests, fragmentation of habitats through road construction, increasing disturbance, overuse of pesticides, and the resultant declines in natural vegetation and prey species due to all of these changes are combining to drive declines in avian and other biodiversity. This kind of habitat loss and degradation is not confined to the Republic of Korea, of course. It is taking place in some form or another throughout the region and throughout the world. And in many countries it is getting worse.

The Proposed Act on Preservation and Use of Biodiversity

Here in the Republic of Korea, newly proposed legislation aims ambitiously to “secure the health of the national ecosystem”. While stating clearly and unambiguously in the Rationale that “the nation’s biodiversity is continuously decreasing due to the pushing ahead of development-centred policies”, the proposed new legislation for now confines itself to:

Setting up and carrying out a National Strategy and Action Plan (which entails the further rationalisation of existing legislation);

Further reporting on the export of species;

Building a National Species’ Inventory;

Founding and running a Centre for Biodiversity;

Building and running a National Information Sharing System on Biodiversity;

Improving management of Alien Species; and

Supporting joint research and training

While applauding the positive elements that have already been included, Birds Korea believes that if the proposed new legislation is to be truly effective it needs to be even wider in scope. It needs to find ways to address all of the “five principal pressures”. Most especially it needs to reduce the pressure of “habitat change”. This is clearly in the national and the global interest.

For reasons outlined above and in our Letter to the Ministry of Environment (sent on July 20th, 2010), we believe that new legislation needs for example:

To help close the gap between international obligations held under e.g. the Ramsar Convention and CBD, and existing local / national policies and development projects;

To incorporate more fully Biodiversity Conservation into wider policy-making bodies/ decisions, and all ministerial briefs;

To strengthen aspects of Biodiversity Conservation in Protected Areas designation and management (with greater restriction of construction and disturbance in already specially-designated areas, including Ramsar sites);

To strengthen the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) by including mandatory use of bio-indicators in assessing potential impacts to sites’/national biodiversity, and by making the process considerably more open and transparent;

To include within the EIA or related legally-binding processes

Recognition of the economic costs and benefits to biodiversity of given development projects, and

Identification of those responsible for any likely decline in biodiversity.

Reduce perverse incentives through an increase in accountability, and through the establishment of a legally-binding mechanism for taxing or fining those responsible for causing biodiversity declines and loss through specific development projects;

Support local and specialised stakeholders’ involvement in EIA and in monitoring and assessing subsequent changes to biodiversity at sites affected by specific development projects through the amendment of existing EIA and related legislation.

Such changes appear to be in line, more than less, with the Articles of CBD and with the aims of the Strategy section of Global Biodiversity Outlook 3.

And changes such as these are needed much sooner than later. According to Achim Steiner of the UNEP, globally “For the past several decades, substantial net gains in economic development have come at the cost of biodiversity and the degradation of ecosystems. More than 60 percent of ecosystem services have been degraded in the past 50 years”.

Perhaps unaware of the ongoing reclamation of Saemangeum and the Song Do tidal-flats, the ongoing degradation of many of the nation’s rivers, and the continuing decline in the nation’s biodiversity, Mr. Steiner in the same interview added that the Republic of Korea is, in his opinion, already “in a leading position when it comes to global environmental issues” (Korea Times interview, Seeds sown for global biodiversity panel).

While this opinion is premature and overly optimistic, effective legislation and a host of upcoming major meetings could indeed help put our nation on track towards global environmental leadership.

With CBD COP10 in October, the G20 Meeting to be held in Seoul in November and the 2012 IUCN World Congress to be held on Jeju, the nation has numerous opportunities to take a leadership role in environmental and biodiversity conservation in the same way that it already shows leadership in other areas.

To correct the nation’s “failure” and to demonstrate this leadership, the nation needs as an urgent priority to reopen fully the sluice-gates at Saemangeum, to cancel further reclamation at Song Do and other internationally important sites, to restrict development in Protected Areas and Ramsar sites, and to scale-back or cancel the Four Rivers Project.

Such welcome and positive decisions, fully in line with existing conservation obligations and the Millennium Development Goals, would signal that the Republic of Korea is ready and willing to give up on the construction-driven addiction of the past few decades, and to lead us all, honestly and confidently, towards a much more bio-diverse and equitable future. We are waiting…

Resources

- KBS. The government’s plan to promote the nation’s tourism and leisure industry (July 15th).

Accessed on July 15th 2010 at: http://world.kbs.co.kr/english/news/news_commentary_detail.htm?No=19291 - Korea Times. Seeds Sown for Global Biodiversity Panel by Bae Ji-sook.

Accessed online at: http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2010/06/113_67383.html - Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea. (2009). Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. In English.

Accessed on July 5th at: http://www.cbd.int/doc/world/kr/kr-nr-04-en.doc - Moores N., Rogers D., Kim R-H., Hassell C., Gosbell K., Kim S-A & Park M-N. (2008). The 2006-2008 Saemangeum Shorebird Monitoring Program Report. Birds Korea publication, Busan.

Online at: http://www.birdskorea.org/Habitats/Wetlands/Saemangeum/BK-HA-SSMP-report-2008.shtml - Secretariat to the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2010). Global Biodiversity Outlook 3. In English.

Accessed on July 10th at: http://gbo3.cbd.int/home.aspx