In total, well over 500 species of bird have been recorded in the Republic of Korea (Birds Korea Checklist 2009). Each of these species has its own optimal habitat, with some species rather more specialised than others - most especially wetland birds and some island-nesting species. Such specialisation makes species especially sensitive to habitat loss and disturbance, so that out of the 34 globally-threatened bird species that occur regularly here, 24 are most often associated with wetlands, 14 of these are ecologically dependent on tidal-flats and estuaries, and a further three are confined as breeding species to small islands. None of these 34 globally-threatened species are ecologically dependent on highly disturbed environments, such as cities, industrial parks, or ship canals.

The global rarity of many such bird species means not only that they and the habitats they depend on need to be conserved (as already obligated by various international agreements and conventions): it also means that they have high value to birdwatchers, “nature tourists” and “ecotourists”.

Birdwatching, Nature Tourism and Ecotourism are big business. Birdwatching contributed 36 Billion US Dollars to the US Economy in 2006 (US Fish and Wildlife Service, July 2009 Press release), and according to Professor Kim Seong-Il of Seoul National University, “‘experiential’ tourism - ecotourism, nature, heritage, cultural and soft adventure tourism, plus sub-sectors like rural and community tourism… could [by 2012] make up 25 percent of the world's travel market, bringing the value of the sector to about $500 billion a year… The Korean government has drafted a plan to invest about $1 billion over the course of four years to invigorate ecotourism… [aiming to construct] 1,000 kilometers of eco-cultural trail, more than 300 eco-friendly facilities (including visitor and education centers), high-quality eco-lodges, and carbon zero eco-culture model cities.” (Korea Herald, April 30, 2009).

Ecotourism as defined by The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) is: “Responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people”. TIES further provides six main principles of Ecotourism. Ecotourism should (see: What is Ecotourism):

Minimize impact.

Build environmental and cultural awareness and respect.

Provide positive experiences for both visitors and hosts.

Provide direct financial benefits for conservation.

Provide financial benefits and empowerment for local people.

Raise sensitivity to host countries' political, environmental, and social climate.

The best ecotourism projects undoubtedly fulfil all of these principles. One outstanding example is the project developed jointly by SAVE International with local partners in Taiwan at the Tsengwen Estuary. After several years of intensive field work, the partnership challenged a proposed industrial complex, which would have destroyed the world’s most important wintering site for the globally Endangered Black-faced Spoonbill Platalea minor. They proposed instead an alternative land-use plan based on conservation and ecotourism. The site was saved; the wintering population of Black-faced Spoonbill and other species dependent on the site were saved; and 1.5 million people (“ecotourists”) visited the wetland in 2001 to see the birds, raising national conservation awareness and creating an estimated 30,000 jobs (B. Butler / SAVE International, 2002). It is perhaps no surprise that the Black-faced Spoonbill has even been featured in TV commercials on CNN promoting tourism to Taiwan.

In stark contrast, several sites used by Ramsar-defined internationally important concentrations of Black-faced Spoonbill here in the ROK have either been destroyed since 2001 (e.g. Saemangeum) or are threatened in the near-future by development projects (e.g. Song Do and Seongsan Po in Jeju). It is extremely difficult to understand the logic of investing a billion US dollars to “invigorate ecotourism” while at the same time many of the nation’s most important and valuable sites for global biodiversity and ecotourism are being destroyed.

It is sadly questionable too if much or even any of the present mass tourism being encouraged at sensitive sites in the ROK (such as Upo Ramsar site or Suncheon Bay) can be called ecotourism. According to the same Korea Herald article, “About 8 million eco-tourists visited Suncheon Bay in 2008 alone, and its direct economic impact is estimated at $60 million.” There have been other impacts too of course. To facilitate the tourists, roads and bridges and a large eco-centre and car park have been constructed all in areas once used by the most famous species there, the Hooded Crane Grus monacha. While there have been positive steps too (including the burying of some overhead wires) and the number of Hooded Crane Grus monacha wintering there has increased over the past decade, this increase appears due largely to an artificial feeding program and to milder winters. Meanwhile, disturbance has increased greatly and other sensitive bird species appear to have declined during the past decade, including the globally Vulnerable Relict Gull Icthyaetus relictus (formerly regular, now apparently absent) and the globally Vulnerable Saunders’s Gull Chroicocephalus saundersi. It is unclear too how much of the money spent by these ecotourists has been returned either to the communities living around the bay or to conservation itself (either at Suncheon or in the nation as a whole). As elsewhere, there has been no large-scale buying of land for protected areas, no well-financed biodiversity-management plans established, and no high-level training courses for wetland managers established, at least that we are aware of.

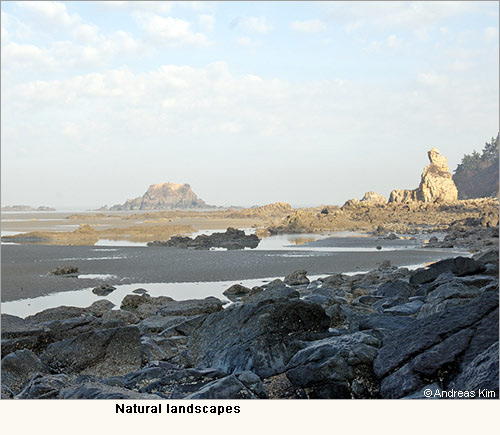

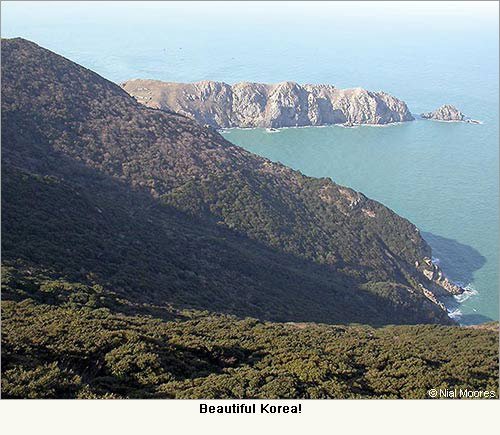

Not only in wetlands, but on many islands too there has been a steady increase in infrastructure, some of it aimed at “nature tourists”, and some of it apparently causing declines in sensitive species. On Gageo Island for example ongoing Birds Korea research suggests that the Black Woodpigeon Columba janthina, a national Natural Monument (and therefore protected by domestic legislation) is intolerant of disturbance. Construction work and the increased flow of tourists compared to earlier years in parts of the island in summer 2009 appear to have led to the loss of several territories of this shy bird, and now plans are in place to construct a new road through a large area of previously undisturbed forest, also used by several pairs of Black Woodpigeon. It might well prove far more economical in the long-term to stop spending vast sums of money on road and other construction, and instead to invest it directly on supporting local communities’ moves towards improving natural resource management, while maintaining local culture. As people’s expectations grow, few nature tourists in the future will choose to travel to concreted islands or coastal areas that lack distinctive culture, natural landscapes or special species.

Already, it is clear that over-investment in infrastructure has damaged both habitats and part of the potential ecotourist experience. While ecotourists from overseas are typically impressed by “the friendliness of people, the Korean style of life, the exotic food (from a visitor’s point of view) and the cultural heritage which all make Korea an enjoyable and interesting holiday destination”, many also realise “that several prime sites for birds are getting destroyed or already have been destroyed by development and reclamation” (Sönke Tautz & Kirsten Kraetzel, Birds Korea Overseas Members, in lit. March 2009).

Spoon-billed Sandpiper and other special Korean birds. © Birds Korea

As recently as 2005, Birds Korea birdwatching-based ecotours would start at Yeongjong Island (in spring) or Song Do (in winter), visit both of the Seosan Lakes, and spend days at Saemangeum (in spring and autumn), or on stretches of shallow, undisturbed rivers used by the globally Endangered Scaly-sided Merganser Mergus squamatus. Any ecotourist hoping to repeat the same trip in 2009 would find most of the Yeongjong sites built over; Song Do mostly-reclaimed, with the last main area remaining targeted for reclamation; a large part of Seosan Lake B now being bulldozed for a resort complex; Saemangeum, a huge stagnant lake, surrounded by salty desert; and many of the rivers already concrete-banked and threatened with further dredging as part of the potentially disastrous Four Rivers project.

Ecotourism if well-managed can be a major part of genuinely Sustainable Development, helping to enhance the national image. It has a huge potential role in the conservation of species and habitats, while providing multiple benefits to local communities, the tourist industry and tourists. Ecotourism is a great way for people to learn about ecosystems, about landscapes and species that have inspired art throughout the centuries, to understand more of the national culture (increasingly lost in the concrete landscape), and to rethink lifestyles. It provides an opportunity to experience the exceptional warmth and energy of island communities, to witness life on the tidal-flat, to see the kind of landscapes that all help to define a wonderful sense of place: “Korea”.

Because of this, for the birds and for the people, Birds Korea will continue to do all that we can to continue to promote genuine Ecotourism as part of a greener future. We hope that you will join us!

special birds and always a very friendly welcome!