While every year is important in its own way, 2010 has special meaning for all who care for birds and other species, for biodiversity. Starting on January 11th, 2010 becomes the United Nations-designated “International Year of Biodiversity” (UN General Assembly Resolution 61/203). It is also the year identified in the Environmental Sustainability Targets of the Millennium Development Goals by which “rates of biodiversity loss need to be reduced” (See: http://www.undp.org/mdg/goal7.shtml ), and new targets need to be set; and it is the year in which the Tenth Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity will be held in Japan in October (http://www.cbd.int/cop10).

2010 can therefore be the year in which concerns for biodiversity loss (i.e. the decline and extinction of species and the systems which maintain life) move much closer to the centre stage of global awareness and political action. Such concern and action are as warranted as they are urgent. As described by the IUCN, “We are facing a serious crisis in biodiversity, the elaborate network of animals, plants, and the places where they live on the planet. And when we talk of animals, we also mean humans”. (http://www.iucn.org/what/biodiversity).

Regrettably, the central importance of species’ conservation to sustainable development, and to climate change adaptation and mitigation, is often ignored. Biodiversity is of course both the life of and in the forest; it is the web of life in the seas, the tidal-flats, the rivers, the grasslands, on mountain tops and in the sky. Biodiversity helps to create and maintain the atmosphere which we breathe; naturally helps to purify the water that we drink and otherwise depend on in so many other ways; and it is biodiversity that contains the species that we eat, either taken directly from the wild or through agriculture, aquaculture and mariculture. Biodiversity is therefore as essential to human life and well-being as the air that we breathe. And yet we continue to neglect, undervalue and destroy it.

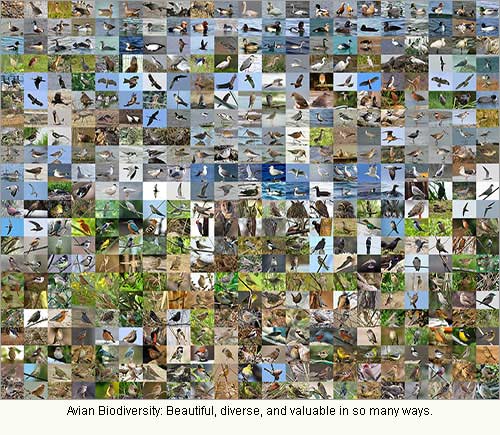

The 2009 IUCN annual review of global biodiversity confirms that already “a third of the world’s amphibians, a fifth of all mammals and 70% of all plants are under threat” (UNEP, 2009), while 1227 (or 12.4%) of all bird species are also now considered threatened with extinction. At present, 192 bird species are classified as Critically Endangered, meaning they are at imminent risk of global extinction (http://www.birdlife.org/action/science/species/global_species_programme/red_list.html).

Only one of these Critically Endangered species is found annually in Korea: the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus. This is a charismatic and highly-specialised shorebird with a global population that has declined from an estimated 2000-2800 pairs in the 1970s, to less than 1000 pairs in 2000, to between 150 and 450 pairs in 2007 (Zockler & Syroechkovskiy, 2008/2010), down to between only 130 and 200 pairs by 2009 (http://10000birds.com/spoon-billed-sandpiper-part-two-interview-with-christoph-zckler.htm).

Like most species, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is (poorly-known yet) rather predictable. It feeds only on a narrow range of foods, and it depends on its habitat differently to other species. Like other species, it also responds to changes to that habitat – either increasing if the habitat becomes more suitable or declining if the habitat becomes worse. Like many species, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is therefore a very valuable and honest bio-indicator, as changes in its population and distribution reveal changes to the environment that we might otherwise miss or choose to ignore. Many such changes are critical to our own species, to our health, culture and economy. Declines indicate the degradation of ecosystems. And extinction reveals that whole habitats are being lost.

“Several hundred” Spoon-billed Sandpiper were formerly counted in the Nakdong Estuary (Gore and Won, 1971), before estuary dam construction in the late 1980s. A peak of only four was counted there in 2009. 280 were reported at Saemangeum on southward migration in the late 1990s (Barter, 2002). A single flock of 31 (which would now represent almost 10% of the remaining global population) was last found at Saemangeum as recently as late May 2007 (Moores et al. 2007). This was one year after the Saemangeum seawall started to kill off most of the tidal-flow and the benthic life on which the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and many other species, including local fishing communities, depended. None were seen at Saemangeum during the whole of 2009 – presumably the first year in millennia that the species has not been present there.

Although the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is also suffering from disturbance and degradation of its Arctic-breeding areas (due to human-induced climate change), in addition to hunting in some areas, the International Single Species Action Plan for the species identifies tidal-flat reclamation and degradation as the main threat to its survival (Zockler & Syroechkovskiy, 2008/2010). With the Saemangeum seawall closed; with the Nakdong Estuary suffering the impacts of barrage closure, reclamation and infrastructure development (and now further threatened by changes in river-use due to the Four Rivers project); and with most other potential sites nationwide lost to the species, the future for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper in the Republic of Korea is bleak. That is, unless existing obligations held under international agreements and conventions are urgently and properly honoured.

The threats to the estuaries and tidal-flats used by the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and other biodiversityare not only within Korea of course. Sites used in China, Viet Nam, all along the Flyway have been degraded or reclaimed in recent decades. One of the last remaining wintering areas for the species is Sonadia Island in Bangladesh, where eight Spoon-billed Sandpiper were counted in January 2009. Even though an alternative development site exists, Sonadia is now targeted for the proposed development of a deep water sea-port, which as intended will be funded by international donors. The first phase of construction would be completed by 2016 and the full development finished by 2055. If constructed, the port would drastically change the habitats used by Spoon-billed Sandpiper, sea turtles, and cetaceans, also threatening mangroves and the marine resources of an area depended on by “hundreds of thousands of community people” (Spoon-billed Sandpiper Recovery Team News Bulletin No. 3, December 2009).

Although declines and even extinction can be driven by natural forces, the rate of extinction is accelerating rapidly, due largely to the rising human population, increasing rates of consumption, and large-scale unsustainable development projects, as at Saemangeum and as proposed at Sonadia Island. The evidence of habitat degradation and loss, the life-threatening cost of present development models, is all around us if we care to look – even through the windows of our homes, our offices, and our cars. It can be seen in the concrete of cities and roads, in the grey horizons and hazy skies. In many parts of the world, including here in Korea, it can even be heard in the growing silence of the seasons.

Economic growth is seen as more or less synonymous with present models of development. If a nation maintains annual economic growth of 5%, then its economy will have more than doubled in size in only twenty years, providing a better quality of life for many. Over a human lifetime of 70 years, the same 5% annual growth, however, would mean that the economy, the amount a nation consumes and produces, will have grown 30 times larger; and by the end of a century, more than 130 times. On a crowded and already resource-stretched planet, is such growth possible or even desirable? Already, it has led to massive declines in marine life and health, a changing climate, and what has been described as an “Extinction Crisis” (Bräutigam and Jenkins, 2001).

Unsurprisingly, humanity’s Ecological Footprint already far exceeds the Earth’s capacity. We are, as individuals and as a species, consuming more than the Earth can produce or regenerate. We are no longer living off the interest. Rather, we are using up the Earth’s “life-savings”. This is clearly not sustainable or wise.

However, rather than modifying the development model to focus on quality of life and genuine sustainability (as called for through the Millennium Development Goals), destructive mega-projects continue to be proposed, increasingly packaged as “green” or “environmentally friendly”.

For example, construction of a city at Song Do in Incheon has already required the reclamation of several thousands of hectares of internationally important wetland. While proposing the designation of some remaining tidal-flats as Wetland Conservation Areas, Incheon City still aims to convert into land the most important remaining area of wetland, an area that supports 13 or more species of waterbird in Ramsar-defined internationally important concentrations. Despite the loss of biodiversity this will cause, Song Do city is still being promoted domestically and internationally as an Eco-city worthy of international accreditation.

Even the construction of 16 new dams and the dredging of 700 km of river as part of the Four Rivers project have been re-packaged as “restoration”. River restoration is indeed needed here in the Republic of Korea. It could be achieved, as in other nations, through the removal of dams and concrete banks, and through the set-aside of large areas of low-lying land to absorb seasonal flooding. Such restored floodplain wetlands would produce numerous benefits. They would improve water quality, reduce downstream flooding, increase water storage, help to conserve biodiversity, and provide beautiful areas for people to visit.

Based in science and an understanding of biodiversity and ecosystem functions, large-scale habitat restoration of this kind will increasingly become a vital tool in reducing humanity’s Ecological Footprint, helping species to increase while for example reducing the threat of human-induced climate change.

The Four Rivers project, however, is not a restoration project. We believe that the Four Rivers project will cause major declines in many species that are ecologically dependent on rivers. These include the Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata (based on Ministry of Environment data, a species that is already declining rapidly at the national level: MOE 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008) and the globally Endangered Scaly-sided Merganser Mergus squamatus.

Depictions of the rivers as proposed after “restoration” produced by the main ministry driving the Four Rivers project try to tell a very different story. Display panels in Mokpo city of the restored Yeongsan River depict boardwalks running alongside a narrow river. While the Four Rivers promises to make several rivers uniformly deep through dredging, this image shows a shallow river with rich wetland vegetation on one side. In the river, close to families of smiling passers-by, swim several usually wary Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus, apparently undisturbed by the massive increase in disturbance. Next to the swans, stand several Eurasian White Storks Ciconia ciconia, a species as yet not recorded reliably in the wild in Korea or East Asia. In the far background, flying over blooming cherry trees, is a flock of Flamingo. This is a family of species typically dependent on highly saline shallow wetlands, not rivers, none of which have ever been recorded in the wild in East Asia!

These depictions are as absurd as they are unscientific. And they reveal the very low levels of concern felt by many for biodiversity.

If biodiversity conservation is so falsely portrayed, how is it possible for anybody to believe any of the other claims connected to these developments?

Clearly, we need to use this International Year of Biodiversity to help improve the situation.

As all of our members know, Birds Korea is a specialised, non-political organisation dedicated to the conservation of birds and their habitats, in Korea and the wider Yellow Sea Eco-region. We work to provide, to import and to export, best information, honestly.

In addition to our usual work, in 2010:

We will open our bilingual gallery of the birds of Korea, containing almost two thousand images, helping to reveal the beauty and diversity of almost 500 of Korea’s bird species;

As part of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Recovery Team, we will continue our work for the Critically Endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper and through survey and literature review we will provide materials on other globally threatened bird species, including the Scaly-sided Merganser. All such work will aim to raise awareness of biodiversity conservation, as a central part of Sustainable Development, and encourage a shift in conservation policy and priorities.

We will continue to promote genuine and well-proven restoration and habitat enhancement approaches, as at the Mokpo Namhang Urban Wetland, and through other projects (in e.g. Busan and Incheon).

And we will continue with the development of the Birds Korea Blueprint for the Conservation of Avian Biodiversity. The Blueprint will close numerous information gaps on species’ distribution, identify population trends in selected species, and through Case Studies examine the strengths and weaknesses of existing conservation initiatives. This report will then be published online and (funds allowing) in hard copy, in time for distribution at the Convention on Biological Diversity conference in October. More details will be provided online and in updates in the coming weeks and months.

2010: a year that is full both of challenge and promise for biodiversity. As always, we welcome your participation and ideas, and thank you for your continuing support!

References

- Barter, M. 2002. Shorebirds of the Yellow Sea: importance, threats and conservation status. Wetlands International Global Series 9, International Wader Studies 12. Canberra, 104 p.

- Bräutigam A. & M. Jenkins. 2001. The Red Book: the Extinction Crisis Face to Face. Published by CEMEX in collaboration with IUCN’s SSC and Agrupacion Sierra Madre.

- Gore, M. E. J. and Won, Pyong-Oh 1971. Birds of Korea. Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society.

- Ministry of Environment. 1999-2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008. Winter Bird Census.

- Moores, N., Rogers, D., Koh C-H., Ju Y-K, Kim R-H and Park M-N. 2007. The 2007 Saemangeum Shorebird Monitoring Program Report. Published by Birds Korea, Busan.

- UNEP. 2009. Extinction crisis shows urgent need for action to protect biodiversity. United Nations Environment Program, Press Release, November 3rd, 2009. Accessed December 2009, at: http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/...Documentclass=602&Articleclass=6360

- Zockler C. & E. Syroechkovskiy. 2008/2010. International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus pygmeus). Series Editor Simba Chan. Published by Convention on Migratory Species & BirdLife International). Accessed Dec. 2009, at: http://www.arccona.org/download/CMS Spoon-billed Sandpiper Action Plan final Nov 2008.pdf